Using Symmetry to Optimize an N-Queens Counting Algorithm

20 Sep 2015 -November 7, 2015 Update: I have now created an interactive visualization tool to walk you through the execution of my algorithm for those of you who are visual learners or those of you who just like cool stuff. Check it out!. If you haven't yet read this post to learn about my awesome N-Queens counting algorithm, I hope you enjoy it!

Several weeks ago, I was introduced to the N-Queens counting problem, and I got to solve it using bitwise operation in Javascript. While it was fun to solve it on my own, I also wanted to see what existing efficient solutions were out there so I could learn how to improve my own algorithm. I stumbled upon this blog by Greg Trowbridge, which presents a Javascript variation of the N-Queens counting algorithm found in a paper by Martin Richards (N-Queens is discussed on pages 2-4 of the paper). This algorithm is highly efficient and has some really cool optimizations that mine didn't have, but I noticed that it didn't take advantage of any symmetry optimizations. Thus began my quest to modify an already awesomely efficient algorithm in order to cut its time down by a half...

This next section gives a brief introduction to the N-Queens puzzle and how bitwise operation can be used to represent a chessboard. If you are already familiar with these, feel free to skip to the section after it.

Introduction to N-Queens and Bitwise Operation in Javascript

The N-Queens problem is a puzzle in which you are given an N-by-N chessboard, and you must place exactly N queens on it in such a way that none of the queens can attack each other in one move (remember that the queen can attack any piece that is in the same row, column, or diagonal). For a large N, just finding one solution can be quite daunting for a human but is a fairly quick task for a computer. The real challenge is counting all of the unique solutions that exist for a particular N. Unlike finding the number of ways to place N rooks on an N-by-N chessboard, which is just simply N! (N factorial), there isn't any known mathematical formula to quickly calculate the number of N-Queens solutions. So the only way to count the solutions is to actually find every solution. This exhausts the computer's resources before the program finishes for very large N. A standard 8x8 chessboard has 92 distinct solutions, and when N=17, there are 95,815,104 distinct solutions! According to this blogpost by Paul Sokolik as of June 2015, the largest N to date for which all the distinct solutions have been enumerated is N=26. The computation took about 9 months using 11 super-computers! This is why this puzzle has become so famous in the computer science community, because every optimization in the computer and algorithm counts.

For those that have not seen the N-Queens problem solved using bitwise operation, here's a brief summary of how the chessboard is represented. Bitwise operators are very fast because they directly operate on individual bits, and a squence of bits can visually represent a row on a chessboard, making bitwise operation ideal for the N-Queens problem. Let's use a 4x4 chessboard as an example. Each row in the chessboard is represented by a single binary number, which is just a sequence of bits. If a queen is placed in the leftmost square of a row, the row is represented by the number 8, which in binary is 1000, because the 1 is in the leftmost spot in this sequence. If a queen is in the 3rd square from the left, then the row is represented by 2, or 0010. The numbers other than 1, 2, 4, and 8 can be used to represent occupation in more than one square, such as 9 -> 1001, or 15 -> 1111. This is useful for marking squares which would cause conflict (squares which are in the same column or diagonal as another queen in a different row). For example, if our conflict sequence is 5 (0101), it would indicate that the only open squares left that won't conflict with other queens already on the board are the 1st and 3rd squares from the left, so those two squares will be the only ones where we try to place the next queen. When you get to a row where every square is in conflict (1111), then you know you've gone down the wrong path which will not lead to a valid solution, so you then backtrack up a row to place the previous queen somewhere else. If the previous queen can't be placed anywhere else, then you must keep backtracking up further to change other queens' positions until you find a solution where all the queens are happy :)

For reference, here is a list of the bitwise operators in Javascript.

A Great Bitwise Solution in Javascript...

I highly recommend reading the above mentioned blogpost by Greg Trowbridge, as the algorithm presented in it is pretty nifty, and the blogpost does a great job of thoroughly explaining how it works. The next section will assume you understand how this algorithm works, so it's a good idea to read the blogpost if you don't.

For reference, this is the solution presented in the blogpost:

In comparing my original solution to this one, I found a really cool optimization here that my first solution didn't have, in the line that says "var bit = poss & -poss". In the binary representation of the variable poss, the zeroes denote spaces in conflict, and the ones are the remaining possibilities. (poss is defined to be the inverse of the conflict sequence, so it is the opposite of what I described in the section above). With a simple binary operation, bit gives us the position of the first square from the right that is available, without having to iterate over each square to check if it's open. For example, if poss is 01010000, then bit is 00010000, and there was no need to waste time and computing resources on iterating over the first four spots to check if they are open (or rather, iterating over the powers of two, which represent the spots). This saves a lot of time when you get to the lower rows where most of the squares have some conflict with queens in the rows above.

However, I noticed that this solution did not take advantage of one optimization: symmetry. So I decided to rewrite it to include this optimization.

...And How I Improved Upon It Using Symmetry

When we have a valid N-Queens solution, the mirror image of it will obviously still be a valid solution. What's more, this actually counts as a distinct solution from the first one, even though all we did was flip the board over! As long as we can be certain that no mirror image is identical to any other solution we've found, then we can just find half of the solutions and multiply the count by 2. When N is even, we can just filter out one half of the first row, knowing that the solutions we miss out on will have their mirror images found when we explore the other half of the row. The case when N is odd is a tiny bit trickier, since we can't divide the odd number of squares in the first row by 2. For all solutions where the queen in the first row is not in the middle square, we can still find half of those solutions and multiply by 2. But it turns out we can do the same thing when the first row has its middle square occupied. When there is a queen in the middle square of the first row, then there can't be a queen in the middle square of the second row because then it would be in the same column as the first queen. Now there are an even number of squares in the second row that are still available! We can just exclude half of the remaining squares in the second row so that we find exactly half of the solutions in which the first queen is in the middle. Add that to half of the solutions where the first queen is not in the middle, and we get exactly half of all solutions, which we then multiply by 2. Voila!

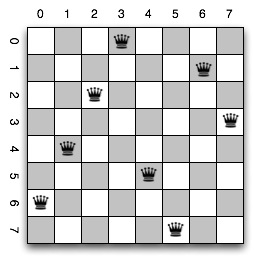

To illustrate:

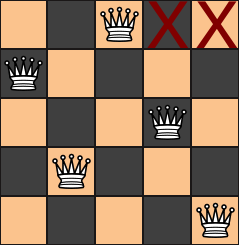

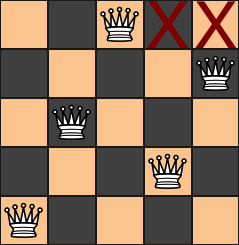

We will exclude the right half of the first row. For odd N, this means up to, but not including, the middle square. This filter will prevent us from finding solutions such as the this one:

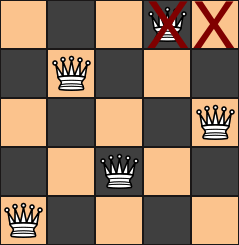

But that's ok, because we will find its mirror image, and multiply the count by 2:

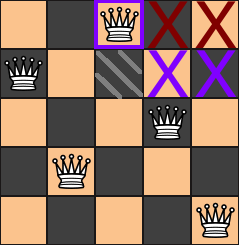

However, this would cause us to double-count solutions where the queen in the first row is in the center square. The following solution and its mirror image would both be counted. And if we chose to exclude the middle square in the first row, then neither would be counted. We want exactly one of these to be counted.

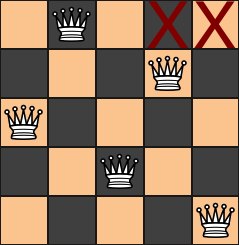

So instead, we will add a conditional filter to exclude the right half of the second row, and this filter will only be applied when the queen in the first row is in the middle square. We will not have to worry about the middle square in the second row because it is in conflict with the first queen, anyway. This way, we count exactly half of the solutions for which the first queen is in the middle, and we can multiply that count by 2.

Here is my revised version of the algorithm that was shown above:

The major change that was made to the algorithm is the addition of the parameters ex1 and ex2 to the innerRecurse function. These are the exclusion filters for the current and next row of the chessboard. On our first call to innerRecurse, ex1 is set to equal excl which is defined above to represent the squares in the right half of the row (up to but not including the middle square for odd N), so our first row in the chessboard will have the exclusion filter. ex1 is then applied to the list of other conflict sequences (ld, col, rd) to eliminate unavailable spots in poss.

ex2 is not immediately applied, but the value stored at ex2 is then passed in as the next ex1 when we call innerRecurse again within itself, while 0 is passed in as the next ex2 so all future calls will have ex1 equal to 0. This ensures that the third row and beyond will not have the exclusion filter. On our first call of innerRecurse, ex2 is set to 0 if N is even and set to excl if N is odd. This is because we only ever want to filter on the second row if N is odd. Furthermore, the filter should only apply to the second row when we have a queen in the middle square of the first row. Thanks to the filter in the first row, we start off the first row with the queen in the middle square. Before we move the queen in the first row to the next square, we set ex2 = 0 right before the end of the while loop. Then the filter will no longer apply to the second row now that we've moved our queen in the first row past the middle square.

The Result

This solution only has three more lines of code than the first one shown above (it seems longer because of the additional comments), and to my surprise, it actually ran in less than half the time than the first solution. I had expected it to take a little longer than half the time, because I figured the few extra steps it takes to optimize on symmetry would cause each recursive call to be slightly slower. I made a few other micro-optimizations which I didn't think would make much of a difference, but I guess they were enough to more than make up for any time lost on performing the extra operations for the symmetry optimization. The micro-optimization that I believe to have made the most difference is eliminating the bitwise operation inside the while loop condition and, instead, performing that operation before the loop so it is not unnecessarily repeated.

Here is a time comparison between the two algorithms (in milliseconds). For each N, I ran each algorithm 5-7 times in the Chrome browser console on my laptop, and I chose the median time for each:

| N | Unmodified Algorithm | Modified Algorithm |

|---|---|---|

| 9 | Half a ms | < Half a ms |

| 10 | 1 ms | Half a ms |

| 11 | 6 ms | 2 ms |

| 12 | 24 ms | 9 ms |

| 13 | 114 ms | 46 ms |

| 14 | 667 ms | 255 ms |

| 15 | 4,077 ms | 1,570 ms |

| 16 | 27,152 ms | 10,447 ms |

For each N in the table, the modified algorithm, which takes advantage of symmetry and a few micro-optimizations, finishes in between a third to a half the amount of time that the unmodified algorithm takes. I originally intended to cut the time down by a half. Mission over-accomplished!

Thanks for reading, and please feel free to leave comments or questions!